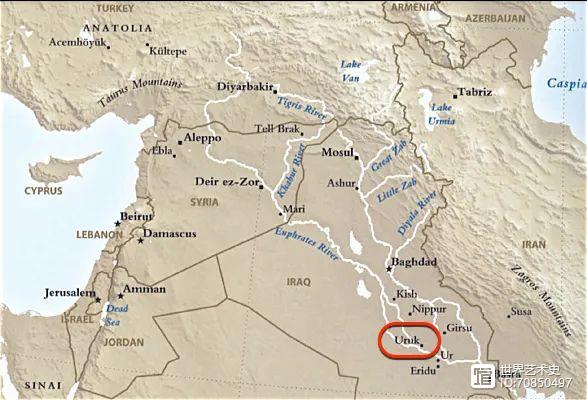

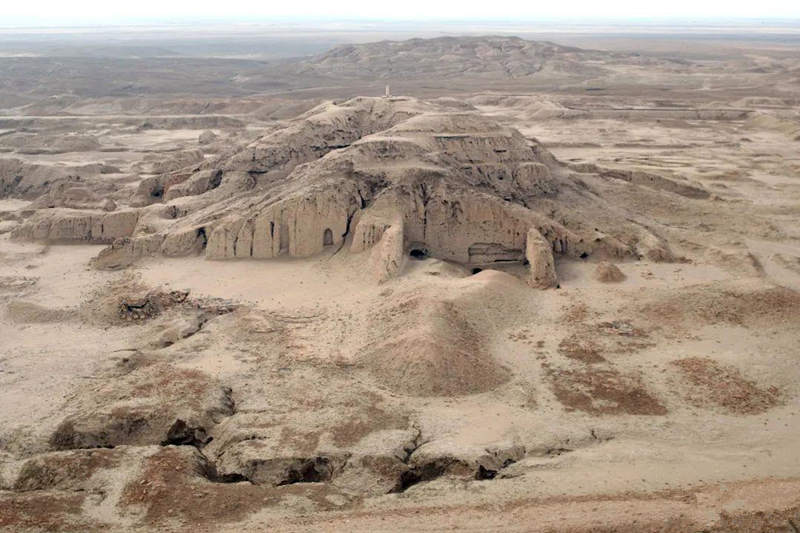

In the cradle of civilization, where the ancient city of Uruk once stood proudly along the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, archaeologists uncovered a treasure that would captivate the world – the Warka Vase. Dating back to around 3200 BCE, this Mesopotamian masterpiece emerged from the sixth excavation of Uruk, conducted by German Assyriologists in 1933-1934. The Warka Vase, also known as the Uruk Vase, transcends its ceramic origins, standing as a testament to the artistry and narrative richness of the early Sumerian civilization. As we explore the intricacies of its carvings, we unveil a visual chronicle that predates even the famed epic of “Gilgamesh.” Join us on a journey through time as we peel back the layers of history woven into the clay walls of the Warka Vase, revealing a story that echoes the cultural heartbeat of an ancient people.

The Warka Vase, also known as the Uruk Vase, was crafted around 3500 to 3000 BCE. It is a snowflake alabaster vase standing at approximately 91.4 centimeters tall and weighing around 270 kilograms.

Uruk was the most important city during the Sumerian civilization in the Mesopotamian region, located in the present-day village of Al-Warka in the Muthana Governorate of Iraq.

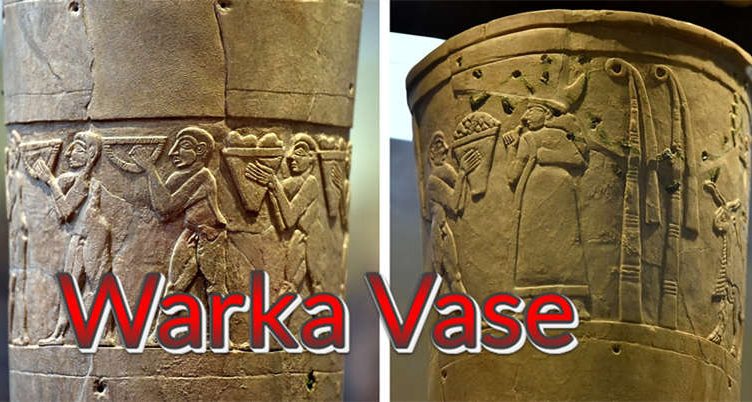

The Warka Vase, shown below, was peacefully displayed in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad before the Iraq War on March 20, 2003. It has a dignified and elegant design with intricate reliefs, indicating its high ceremonial significance.

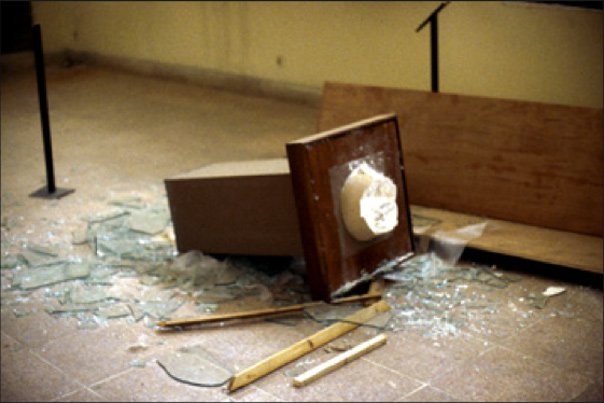

Here is the appearance of the Warka Vase after the Iraq War:

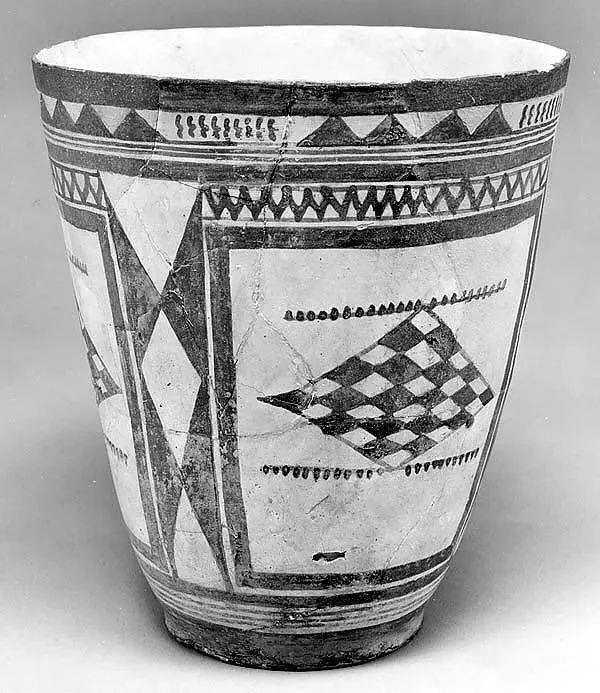

The Warka Vase was discovered by German Assyriologists during the sixth excavation of Uruk in 1933-1934. Initially found in fragments, it was meticulously restored, revealing detailed carvings on its body. Unlike another vase discovered simultaneously, the Warka Vase was in better condition. Archaeologists also noted ancient repairs on the Warka Vase, similar to the previously mentioned large cup unearthed in Susa, Iran, suggesting its importance and care in ancient times.

The Warka Vase, along with many other artifacts, was looted from the Iraq Museum between April 10 and April 12, 2003, in the aftermath of the Iraq War. Thieves toppled display cases, separated the Warka Vase from its previously restored base, and stole it. Two months later, on June 12, three unidentified individuals approached the museum’s security gate in a red Toyota. They unfolded a blanket from the car’s trunk, revealing the Warka Vase broken into 14 pieces. The individuals handed it over to the Americans and disappeared. The base and upper rim of the vase suffered severe damage.

In February 2015, after 12 years since the war, the Iraq Museum reopened, and many artifacts were gradually recovered. However, treasures like the Warka Vase couldn’t be restored to their original state. The unpredictable factors during wartime make it challenging to protect both human lives and cultural heritage. While the U.S. military was criticized for inadequate protection, as a collective, humanity often fails to learn from historical lessons.

The Warka Vase is considered a treasure of the Iraq Museum, the 11th largest museum globally. Its significance lies in Uruk being the largest city of Sumer, the vase being excavated from the temple complex dedicated to the goddess Inanna, the protector of Uruk, and its historical importance to the ancient Near Eastern civilizations.

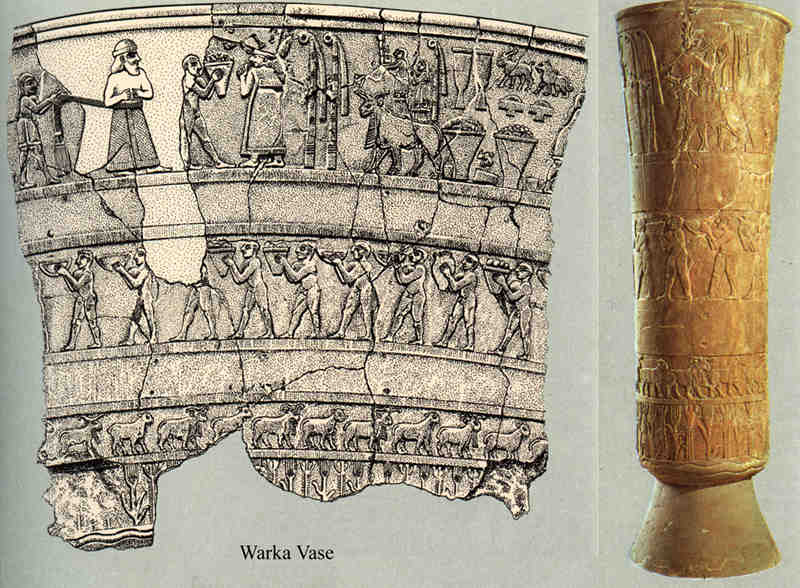

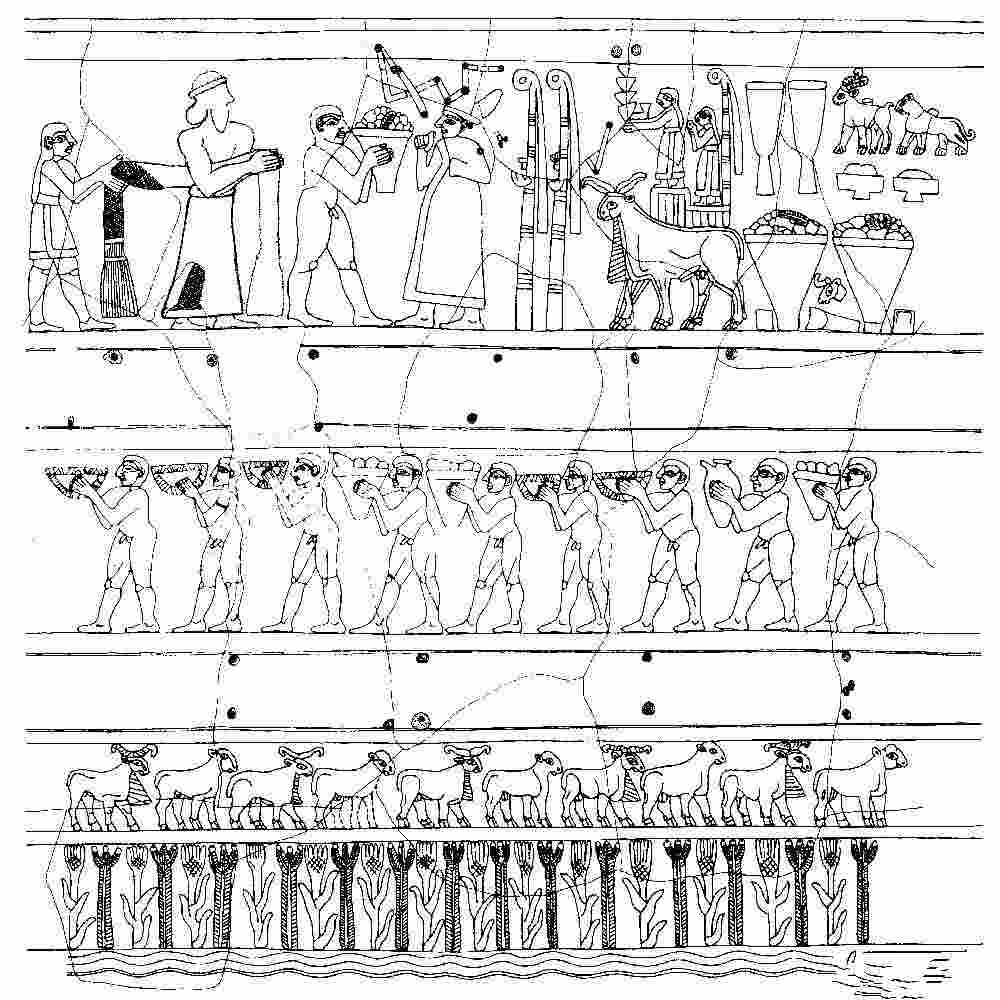

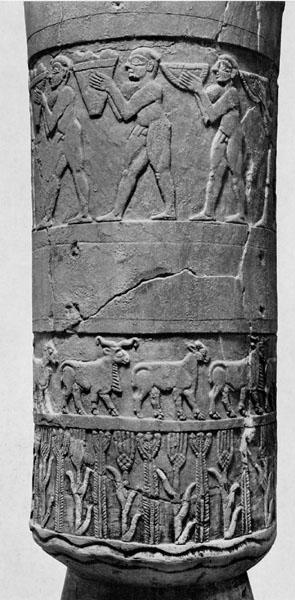

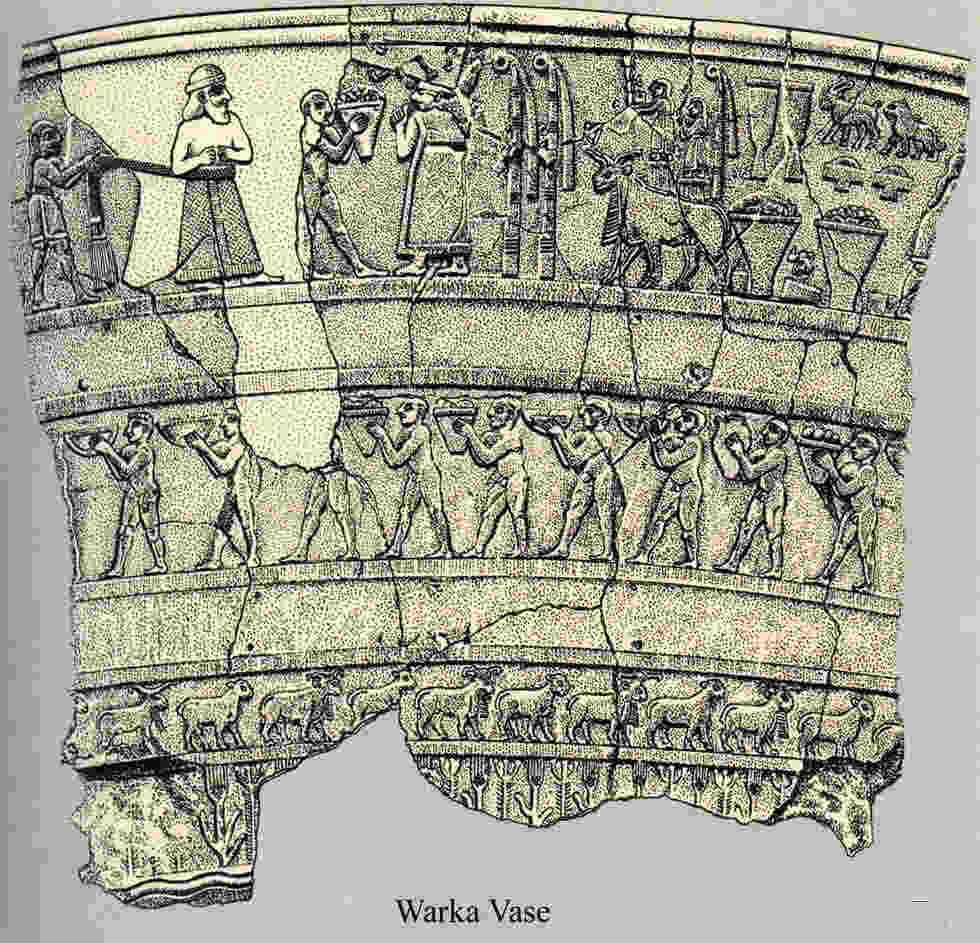

The Warka Vase features reliefs covering its entire surface, divided into four parallel registers. The complexity of the relief themes increases from the bottom to the top.

The bottom register displays a decorative wave pattern, representing the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, with alternating crops, possibly barley and flax or reeds. The rhythm continues into the animal frieze above, where rams and ewes alternate, creating a pastoral scene. These two bands reflect the fundamental state of human society transitioning to agriculture.

The upper part of the animal and plant frieze was likely painted but has faded over time. Above it are nine nearly identical men, carrying vessels containing important Mesopotamian agricultural products: fruits, grains, and wine. Given the lower social status associated with bare feet, they might be servants or slaves.

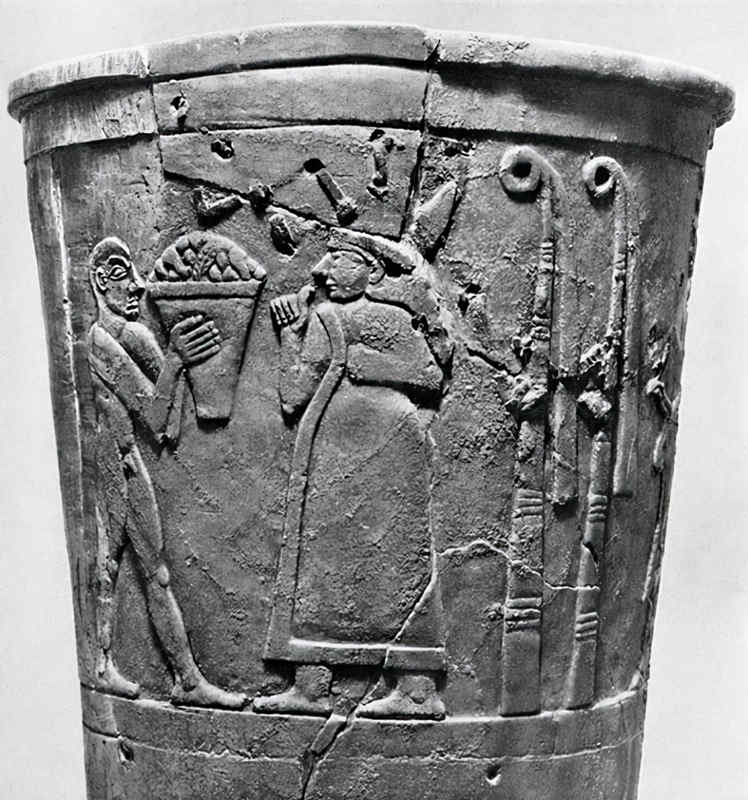

The top register is the widest and most complex. In the center, there appears to be a depiction of a man and a woman facing each other, with a smaller man holding a container filled with agricultural products. The woman, likely representing the goddess Inanna, wears a gown and crown, and the scene was partially restored in ancient times.

Behind Inanna are two bundles of reeds, symbolizing the goddess. The male figure opposite her is mostly damaged, but considering similar depictions of kings from that period, he might be reconstructed as a king wearing a robe, beard, and headband. The tassels on his robe are held by a smaller man behind him, possibly a steward or attendant wearing a skirt.

Behind the reeds following Inanna, there is a complex scene. Two rams with horns and beards carry two pedestals, each supporting a statue. The left statue bears the cuneiform sign “EN,” meaning “high priest” in Sumerian. The right statue stands in front of another bundle of Inanna reeds. Behind the rams is a series of offerings, including two large vessels resembling the Warka Vase itself.

The interpretation of the entire scene is open to discussion. A simple explanation suggests a Uruk king making an offering to the goddess Inanna. A more intricate interpretation proposes that the king, as the high priest of Uruk, has a sacred marriage with the goddess. The combination of real and sculpted figures ensures the fertility and prosperity of Uruk, as depicted in the carvings behind the rams. The evolving relationships among priests, gods, and kings are explored in a previous documentary on Sumerian civilization.

From the perspective of art history, this vase represents one of the earliest instances of complete narrative art. It develops from the domain-setting elements in the Susa beaker to layered narrative forming a complete “story,” echoing the appearance of recorded human history in the earliest Mesopotamian epic, “Gilgamesh.”

END:

As we stand on the threshold of the past, the Warka Vase beckons us to reflect on the profound insights gained from this archaeological marvel. This ancient vessel, with its intricate carvings and layered narrative, serves as a bridge connecting us to the dawn of human civilization. Through the lens of the Warka Vase, we gain a deeper appreciation for the cultural complexities, religious rituals, and societal transitions that marked the Sumerian era.

The Warka Vase not only offers a glimpse into the daily lives of our ancient predecessors but also sparks the imagination, inspiring a renewed sense of wonder about the human journey through time. Its reliefs become a visual testament to the resilience and creativity of early civilizations, inviting us to contemplate the universality of human experiences across millennia.

As we ponder the lessons embedded in this clay artifact, it becomes evident that the study of such archaeological treasures holds the key to unlocking the mysteries of our shared heritage. The Warka Vase inspires a continued dedication to archaeological research, encouraging scholars to delve deeper into the annals of history, unraveling the stories hidden within the earth.

In essence, the Warka Vase serves as a guiding light for future archaeological endeavors. Its legacy prompts us to ask more questions, seek more connections, and embark on a quest to unveil the untold narratives buried beneath the sands of time. In the pursuit of understanding our past, we find inspiration for shaping a more enlightened future, where the echoes of ancient civilizations continue to resonate in our collective consciousness.

More UFOs and mysterious files, please check out our YouTube channel: MysFiles

Mysterious Stone Spheres around the world – Costa Rica, European forest, Russia, Kazakhstan